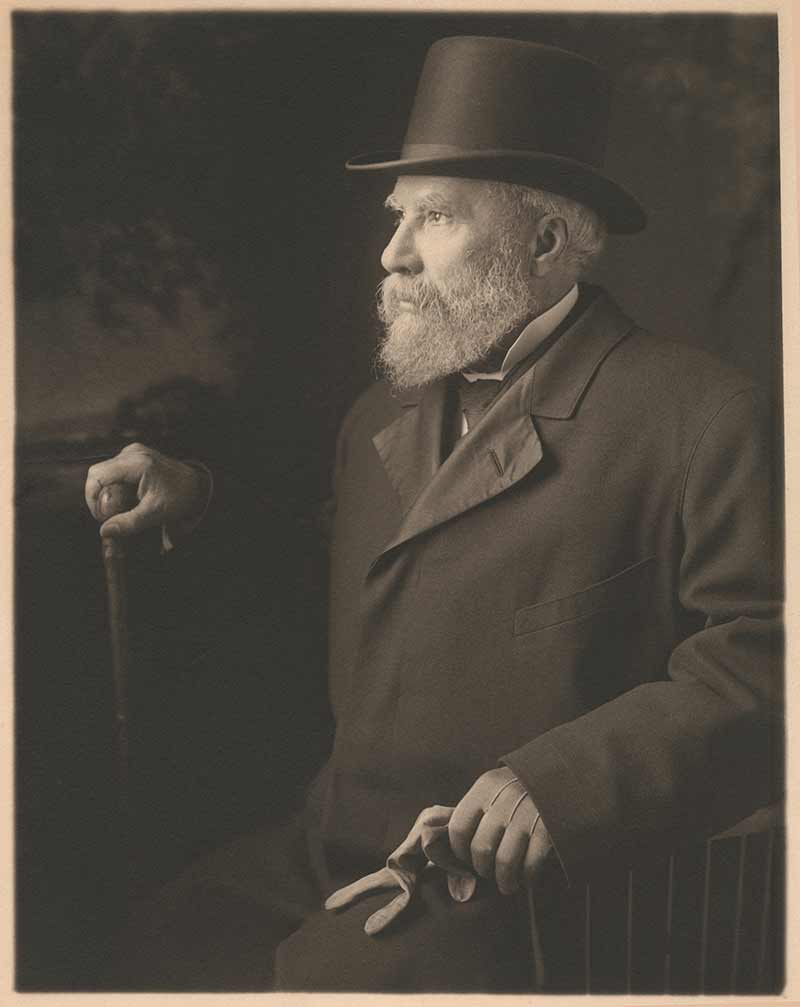

James J. Hill

Learn about the life and legacy of this railroad executive who was a pivotal force in the transformation of the Northwest, earning the name “The Empire Builder.”

Childhood

Born in southern Ontario on September 16, 1838, to Irish immigrant parents, young Hill suffered a bow and arrow injury at age nine and lost sight in his right eye for the rest of his life.

Hill's father died when the boy was 14, so Jim Hill began clerking in local shops before setting off to seek his fortune. He began his career in transportation in 1856 as a 17-year-old clerk on the St. Paul levee.

Railroads

After 20 years working in the shipping business on the Mississippi and Red rivers, Hill and several other investors purchased the nearly bankrupt St. Paul and Pacific Railroad in 1878.

Over the next two decades, he worked relentlessly to push the line north to Canada and then west across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. Renamed the Great Northern Railway in 1890, it remained the "great adventure" of Hill’s life. "When we are all dead and gone," he said, "the sun will still shine, the rain will fall, and this railroad will run as usual."

The 1893 depression saw the collapse of many businesses, including railroads, throughout the United States. Hill took drastic cost-saving measures to keep the Great Northern operating, but the pay cuts to railroad workers proved too much to bear. Workers went on strike that year. Surprisingly, at the end of arbitration Hill accepted most the workers’ demands. It was a notable victory for the young labor organizer Eugene Debs (and occurred a few years before the more famous Pullman strike in Chicago) and marked a significant change in workers' rights.

With the return of prosperity and the wave of trust-building and consolidation in the late 1890s, Hill’s problem became one of how to retain control of his vast railroad holdings. As he bought smaller lines, his wealth and power expanded greatly. Early in 1901 he joined with J. P. Morgan to buy control of the Northern Pacific Railroad — control contested by E. H. Harriman of the Union Pacific in an epic stock market battle in May 1901.

On November 1, 1901, Hill, Morgan, and Harriman announced the formation of the Northern Securities Company, a holding company formed to control the Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, and the Burlington lines. Not for the first time in Hill's career, competitors became partners.

The $400-million merger consolidated all major rail lines in the northwest quarter of the nation. The move was politically unpopular and in clear violation of Minnesota statutes. It was immediately challenged in court by Governor Samuel Van Sant. In February 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt began prosecution of the Northern Securities Company under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

At Hill’s insistence, the case was tried in St. Paul at the Federal Courts Building (now Landmark Center). Hill was represented by, among others, the law firm headed by Frank B. Kellogg. The case was carried to the US Supreme Court, and Northern Securities was declared to be in restraint of trade in a 5-4 decision in March 1904. It was a bitter blow to Hill, and the decision marked the role the federal government would often take in breaking up corporate monopolies in the 20th century.

Other business interests

Hill pursued a broad range of other business interests: coal and iron ore mining, Great Lakes and Pacific Ocean shipping, banking and finance, agriculture, and milling. In later years, he explained his economic philosophy in the book Highways of Progress and continued the campaign to convert the farmers of the Northwest to the principles of scientific agriculture, often testing breeds of cattle and strains of grain at his own farms.

Marriage and family

In 1864 Hill met a waitress who was working at the Merchants Hotel in St. Paul, where he often ate. Mary Theresa Mehegan, born in 1846 in New York City, was the child of Irish immigrants who settled in the frontier town of St. Paul in 1850.

Hill sent Mary to finishing school in Milwaukee before their marriage in 1867 to prepare her for the impending change of stature in her life. Over the next 18 years they had 10 children: Mary, James, Louis, Clara, Katherine (who died in infancy), Charlotte, Ruth, Rachel, Gertrude, and Walter.

Four of the daughters were married in the mansion, and five children later had homes on Summit Avenue. Louis succeeded his father as president of the Great Northern Railway, and lived with his family next door at 260 Summit Ave.

Personal life

Physically, Hill was short and barrel-chested, with a long torso and short legs. People commented on his piercing gaze and said he held their attention with his quick, animated speech, gesturing expansively and jabbing the air with a hand or finger to make his point. He was well-known for his blunt, direct manner, and many commented on his occasional flashes of humor. He was a voracious reader of nonfiction, although there are references to Hill “lustily” singing ballads based on the poems of Robert Burns.

In rare moments away from work, Hill devoted himself to amassing an impressive collection of French landscape painting showcased in the two-story art gallery of his Summit Avenue mansion. He cherished summers at the family's North Oaks farm and an annual spring trip to his hunting lodge in Quebec for salmon fishing.

His philanthropy included generous gifts to colleges and universities, and prompt responses to victims of disasters, such as the sinking of the Titanic, the Hinckley fire, and the San Francisco earthquake. Political contributions favored policies over party, and Hill was frequently frustrated when candidates failed to fulfill campaign promises.

Death in 1916

After amassing a personal fortune estimated at $63 million and over $200 million in related assets, James J. Hill died in his Summit Avenue home on May 29, 1916, one of the wealthiest and most powerful figures of America’s Gilded Age.

At the end of his life, Hill was asked by a newspaper reporter to reveal the secret of his success. Hill responded with characteristic bluntness: "Work, hard work, intelligent work, and then more work."

For further research

In the MNHS Shop