Milling Changes Farming

Wheat in shocks near Fort Snelling.

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Location no. SA4.52 p29

Until wheat became king in the 1870s, Minnesota farmers didn't generally expect to become rich off their crops. They grew food for their own family, feed for their livestock, and a few acres for cash. They took their own wheat to a local mill that ground it into flour for the family's cooking.

Once the flour milling industry in Minneapolis caused a demand for spring wheat, farmers saw the chance to make more money than they had ever imagined. They shifted their fields to wheat for sale, with only small gardens for themselves, and began buying things they had always made themselves or never needed.

Bonanza Farms

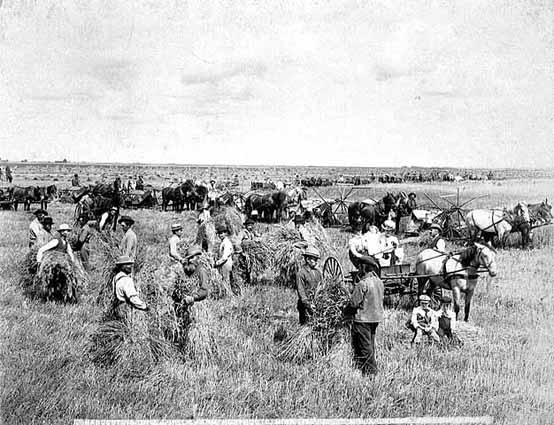

Harvesting on James J. Hill's farm at Northcote, 1901.

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Location no. SA4.52 p45, Negative no. 10083

The same rich soil, access to rail transportation, and demand for spring wheat that attracted settlers also attracted big business in the 1870s and 1880s. Major stockholders in the failed Northern Pacific railroad found themselves as owners of thousands of acres (settlers had to live on the land five years to get 160 acres). They hired managers, bought expensive machines, and took on large crews of temporary labor to work the fields.

Bonanza farms accounted for only 2% of the midwest's farms, but they efficiently produced millions of bushels of wheat for Minneapolis's hungry mills. They also quickly cut open the prairie and robbed it of essential nutrients, partially leading to the decline of the giants in the 1890s.

"The whole summer of 1887 I worked on a section of Dalrymple's immense farm in the Red River Valley of the North. Besides myself there were two other Norwegians, a Swede, ten or twelve Irishmen, and a few Yankees. We were twenty-odd men all told on our little section—but we were a mere fraction of the hundreds of laborers on the whole farm.

The prairie lay golden-green and endless as a sea. No buildings could be seen, with the exception of our own barns and sleeping shed in the midst of the fields. Not a tree, not a bush grew there—only wheat and grass, wheat and grass, as far as the eye could see....

No birds flew overhead; there was no movement except the swaying of the wheat in the wind; no sound but the eternal chirrup of a million grasshoppers, singing the prairie's only song....

We worked a sixteen-hour day during the wheat harvest. Ten mowing machines drove after each other in the same field, day after day. When one field was finished, we went to another and laid it down as well. And so onward, always onward, while ten men came behind us and shocked the bundles we left. And high on his horse, with a revolver in his pocket and his eye on every man, the foreman sat and watched us...."

—Knut Hamsun

Knut Hamsun, "On the Prairie: A Sketch of the Red River Valley" (translated by John Christianson), in Minnesota History, Sept, 1961. (Originally published in 1903 as "Pa Praerien" in Kratskog).