Oral Histories

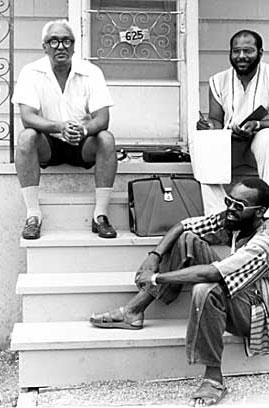

Between 1970 and 1975, the Minnesota Black History Project interviewed thirty-two Black Minnesotans. They covered a range of topics, among them family, social activities, political organizations, and community involvement. Five of those interviewed discussed the Duluth lynchings and its effects on themselves and on their communities. Audio excerpts from those interviews are now available to users of this site.

Oh, I was out in West Duluth visiting with my brother, and we saw these headlines. I assumed then that there would be a lynching, and there was. The mob. . . There were six prisoners in jail, but at daybreak they had only lynched three. And they were all exhausted. But there were women and children in the mob.

And then after. . . The next night, after the mob — the white people — said they were going to run all the niggers out of town. And I remember, I had just come back from the war then, you see. I didn’t have a bathrobe. I had an army raincoat. And we’d decided that we’d just barricade ourselves in our house. I was the only one who had a gun. I had a .45 Colt automatic that I’d brought back from the war. I still have that gun by the way.

In the night, the sheriff and. . . There were several, quite a few concerned white people about our welfare, and wanted to make a relationship with us. But we’d decided to go it on our own.

There was a telegram come to our house. Someone had heard something about it and was concerned about the relatives. The messenger. . . In those days they didn’t telephone, they brought the telegram; delivered it.

And I was rooming with these people. It was a family. This Rodney who I told you about. I was rooming at his mother’s house. She was a widow woman.

When the door rang, he who was older, Wallace who was older than I, said, “See who’s at the door, Ed.” So I put on my raincoat and had these pockets that go through the army raincoat, and I put the .45 Colt automatic down in there and cocked the trigger back, and I went to the door.

And there was a white lad out there. And I said, “What do you want?” He said he had a telegram from Western Union. But if he would have tamped his foot I would have murdered him. We were that tense.

Another thing I guess I’ll never forget is when the forest fires — when the lynching occurred in Duluth. That was 1920.

. . . My father had had me join him in a trip south in 1919. We were gone for about four months. And in talking to the people in the South, he was trying to encourage young people to come north, to go North and go to school and he had a way of saying how white people don’t favor you, it isn’t that they like you, but you’ll be sure of a fair trial. That’s one thing you’ll be sure of, you can get a fair trial. So this particular day I went to the post office to pick up the mail as we always did after the limited train came in and no one spoke to me.

. . . I thought it was queer because by this time I had been there — I’d been there over a year and people had a way of saying good morning and when I got to the post office, they — the postmaster would joke about the amount of mail I got personally because I had been on this trip and there was a lot of people writing me. And I didn’t know what it was. I went back to the office and my boss was on the phone with Duluth, and he swung around and he said, “There’s terrible trouble in Duluth. They’re calling out the National Guard.” And I asked why and he said, “It’s a race riot.” And I couldn’t imagine that because knowing the Negroes in Duluth they’re not that militant sort. But then he said then that they’ve lynched some Negroes. Well, I couldn’t reach my folks by phone and so I went through that day and then I realized what it was, the animosity in the town [Moose Lake]. That the feeling of — their reaction seemed to be that they would have liked to have been in on the lynching party.

. . .My father was furious about it — of course he was very upset, particularly because it was happening about four blocks from our home, outside the Shrine Temple, and as he walked down the hill that next morning to work the bodies had been cut down and were lying there at the foot of this telegraph post. And there was a circus in town and fourteen Negroes were taken off a train that was ready to pull out with all the circus paraphernalia late that night. And this white girl claimed that she had been raped by fourteen Negroes and she’s supposed to have identified these four. They had a kangaroo court. The Chief of Police was out of town; the mayor was out of town. And I understand that they got their necktie party up by parading up and down the main street, and no one stopped them. No one seemed to. . . But I know that it was one of the things that my father deplored because he went out hunting and had shotgun, rifle and different things. And he always kept them ready; they always — and I know that if he had had any inkling of it he would have tried to have done something about it. And I think he felt cheated in a way.

. . . One good thing that developed. There were a few white people who wrote letters to the newspaper deploring it and my father was able to start an NAACP branch. He had tried before but the Negroes weren’t interested and they said that he was trying to segregate them. Because we have no trouble here in Duluth, so we don’t need an NAACP branch. But he had no trouble after this happened. And he brought — our first speaker that he brought was Dr. Du Bois.

A circus came to town, and in those days when a circus came to town it was sort of a holiday to go out and watch the — what do you call them — the roustabouts put up the big tent [Note: The circus was closing down, not setting up]. It was quite a knack. . . It was quite a thrill, and concessionaires would be open, and these fellows that they called roustabouts generally were blacks from the deep South. And what happened was that that night a woman claimed that she was raped. Now the interesting part about that was she never reported the rape until the following afternoon. And her boyfriend reported it. And they were having lynchings around the country. If you read the papers of that day, you’ll find that every week there was a lynching someplace in the country. So it got fanned up here in Duluth and they estimated as many as 9,000 people actually witnessed these lynchings. We’re speaking about a city that at that time probably was about 85,000, 80,000.

. . . They took them out of the [inaudible]. The circus moved to Virginia. And they went up there and arrested a number of them and brought them back to Duluth. And when the lynching fever came along the people did ask the police at that time, were they going to move them to Carlton County so there wouldn’t be a lynching? And they apparently were ignored by the police department. And then when the drive came on the police department, they just took the men out. They held some kind of kangaroo court. They didn’t take them all out; they only took three for some reason. Something took place inside the jail. And they hung them right in front of the Shrine Auditorium.

. . . Well the editorials in both the News Tribune and the Herald, which were different papers in those days, were very much appalled by the lynching and so were many of the better class people were really shook up that this took place here because it’s not the best thing to take place in your city of this size. Most lynchings that were happening were not happening in cities as large as Duluth. I mean police departments are usually adequate to take care of it, except possibly in the Deep South.

Now, when this lynching happened they were really afraid. Now, I can remember this, that they were so afraid, a lot of them from Duluth went over to Superior side, left their homes. They were so afraid to stay in their homes. And I was told some of them hit the bay out there and went right across, they didn’t look for dry land, they were so afraid. They kept themselves hidden from being seen, you know, out in the streets. They were afraid to go out. They were even afraid to go out. But later the laws of the city here and the different officials said there wouldn’t be any more lynchings. They kind of got them where they would have more confidence that they could come back to their homes. But they were really shook up there at that time.

Well, as I say, we came here in ’23. But I heard it from different sources. And so many people did barricade themselves in their homes, you know, and some got out of town; went across the bay to Superior. But it kind of settled down, you know. But it lasted for quite awhile. At the time we came here, you know, some of them still had that fear, because as I said before, this friend of mine said she never wanted to stay in Duluth after the lynching.